Primary Education, the true victim of a nation in conflict

“Education is not a way to escape poverty; it is a way of fighting it.

The words of Julius Nyerere, the first leader of Tanzania (1960), are as true today as they were when he spoke them more than four decades ago, we still see that the attainment levels of basic education in much of the world remains alarmingly low. In large part, this is due to an unwillingness from some quarters to accept that the best way to address the plethora of issues that most citizens face is through proper and sustained investment in education. Every metric, from public health to the ability to attract foreign investment, is improved when the educational outcomes of citizens are improved. It is the proverbial rising tide that lifts all ships.

The quality of education offered in a nation’s primary schools is an important determinant of whether or not parents will bother to enroll their children and keep them enrolled until they complete primary school. It affects whether or not girls in impoverished families are subjected to early marriage, early motherhood, and increased rates of infant and maternal mortality1. If primary school graduates are still functionally illiterate, parents are unlikely to accept the opportunity costs associated with sending a child to school when their labour could otherwise be used at home or in the informal marketplace.

When we talk about the quality of education, we are not limiting our scope to western style education. A quality primary education need not take the western approach; rather, it should be adapted to the realities of the communities. In communities where most students do not matriculate to secondary education, there is little tangible benefit in teaching Greek mythology when what the students need are solid math skills, functional literacy, and basic entrepreneurial skills2.

A quality primary school education must provide children in low- and middle-income countries with increased economic opportunities and the skills to live more healthily. In countries still healing from the devastation of violent conflict, schools must also act as a place where communities learn to move past old grudges, reaffirm their national identity and share equally in the rebuilding of a more prosperous nation. This will require nations to train teachers differently, to hold them more to account, and to design a curriculum that focuses the eyes of the young on the future of their nation and not preferentially overseas. The result of a country failing to do so is the ‘brain drain’ experienced by many developing nations as some of the best and brightest set off for greener pastures.

Because the detrimental impact of ‘brain drain’ is greater for developing nations, it is important to create favourable economic prospects in tandem with an academic environment that focuses students on what they can do to effect change and growth in their own country, city or village. It is a tall order that requires high expectations and significant investment, but it can and must be done.

Investment in education by nations rebounding from conflict must be specific, purposeful, and targeted. It will require individuals with the fortitude to examine everything they think they know about ‘school’ and how education can stimulate a community. Investment in education is also an investment in related areas of the economy, such as the garment industry, sanitation, local agriculture, construction, and infrastructure. Schools may benefit from being ‘off the grid’ so that lessons are not interrupted by power outages, thus spurring the growth of alternative energy industries and other new industries.

School buildings will need to be redesigned to make them fit for purpose, easy to repair for locals, and adaptable to the needs of the wider community. School supplies will need to be produced nationally and transported locally. Teachers will need training, desks made, and uniforms sewn; in short, an education plan is an economic plan.

Conflict

When discussing the effects of conflict on education, it is tempting to define conflict as violent political and social upheaval. We think of armed conflict and sectarian strife. And while insurgencies, civil wars, tribal conflicts and even blood vendettas between rival clans are good examples of conflict in action, the definition should not be limited to lethal violence.

Conflict can be non-violent. It can include sporadic or even tightly contained and non-lethal aggression between rivals. Here we will define conflict as any contentious situation whereby two or more rival factions compete for social, political, or economic dominance in a way that is disruptive to the cohesion of the basic fabric of society. The roots of these conflicts are varied but immaterial for our purposes.

Children of conflict

While examining the effects of conflict on education, it is also important to define who we are talking about when we say, ‘children affected by conflict.’ Again, the default definition is limited to children whose education is interrupted or who are physically displaced by conflict. While these are the easiest to identify, they are not the only ones who are affected by conflict.

Often children who live in areas neighbouring conflict zones are also negatively impacted by the conflict. New security policies, limited services, or an influx of children escaping the conflict can have a negative impact on the education they are receiving despite not being directly involved in the conflict themselves.

We must also include children who have never had the opportunity to attend school because of the destruction of the infrastructure for education. Demolished infrastructure is more than just destroyed school buildings. This means that the ability to access textbooks, the availability of teachers and the physical safety of students and teachers as they travel to and from lessons is not guaranteed. In such cases, though armed conflict may have ended the effects of conflict on education remains.

For our purposes, when we say ‘children affected by conflict’ we are identifying children whose education is interrupted or halted altogether by conflict. This includes children whose education is cut short due to schools closing, lack of teachers, lack of access to books, or displacement.

The numbers

In 2012 UNESCO reported that approximately 58 million primary school-aged children were not attending school3. It is important to note that these numbers only include children under the age of 12 and do not account for children in middle grades or secondary school. They also do not include students in vocational or tertiary level education.

Of these estimated 58 million, 23% attended school in the past but left, 34% will return to school in the future, and a staggering 43% will never have attended school4.

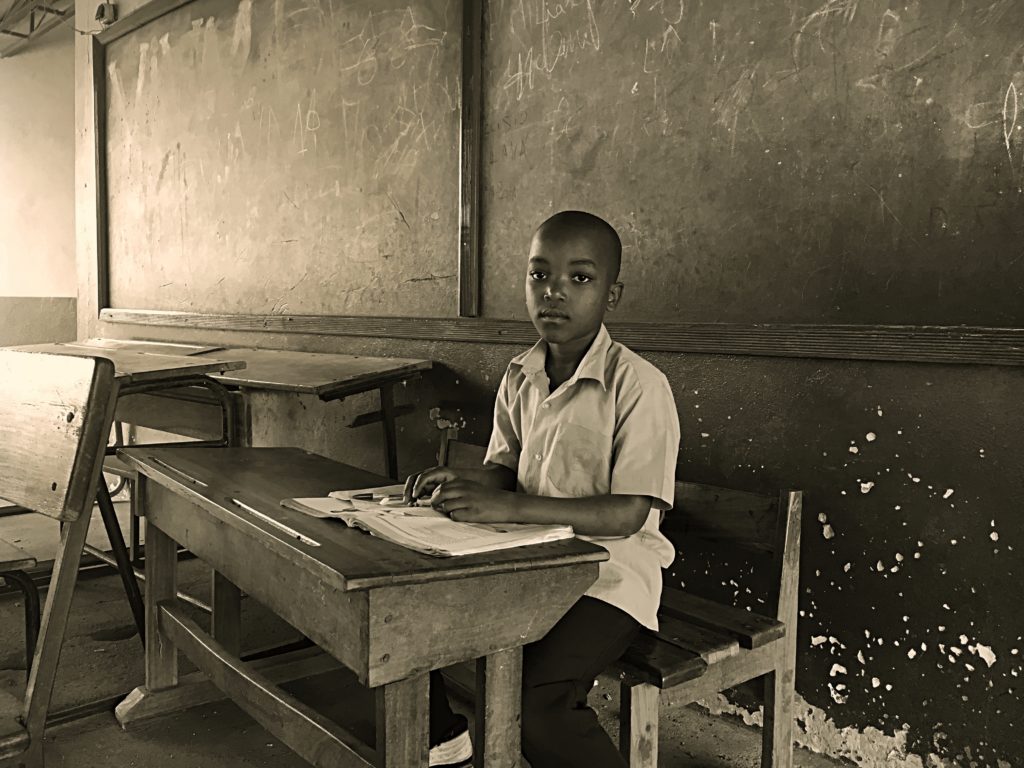

The bulk of these children, 39 million, came from just 33 countries affected by conflict. Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Pakistan account for nearly half of all out-of-school children.

The real cost of such conflicts is impossible to quantify. However, you can obtain a good estimate of the investment needed to resume a national education programme by combining considerations such as the destruction of education infrastructure and loss of economic productivity. Appropriate investment is necessary to avoid creating a ’lost generation’ of uneducated or under-educated adults. Focusing on Nigeria, DRC, and Pakistan alone, we can get a clear picture of what most conflict-laden countries experience when trying to rebuild or maintain an education system.

An estimated US$1337 million, capital and staffing, were lost in the education sector due to conflict between 2009 and 2012. But, as previously stated, the losses go far beyond the logistics of rebuilding schools and hiring new teachers. For many students, the conflict may end their education altogether; many young boys are recruited as child soldiers; many young girls are kept at home to help tend to injured, sick, or ailing family members as well as to help with domestic work.

The fear of violence and uncertainty will prevent parents from enrolling children in school. Also, poverty will keep many young people out of school long after the conflict has ended. This is to say nothing of those children who never had a chance to step foot inside a classroom.

By calculating the lost economic benefit of children whose academic careers are ended by conflict, we see an even greater loss to these countries5

When talking about girls specifically, there is a direct correlation between education and fertility – the lack of education or decreased quality/value of education is directly linked to increased early fertility. According to the World Bank, early marriage is the cause of three out of every four girls leaving school before the age of 18. These child brides will face a 9% decrease in lifetime earnings and higher maternal and infant mortality.

A decrease in infant mortality is expected to benefit the global economy by US$90 billion annually by 20307. While no single factor can prevent early marriage, the availability of education that is valuable to the communities involved can have a significant impact in reducing their frequency. The World Bank estimates that the global economic loss from uneducated girls runs annually into the trillions of dollars.

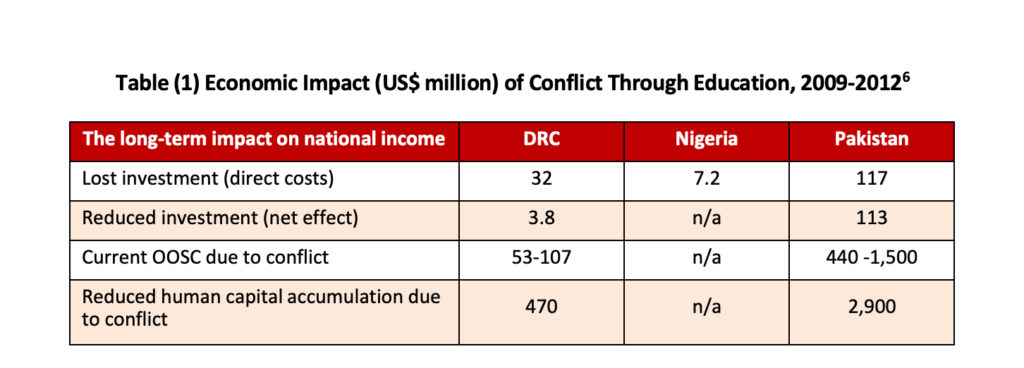

But what of those children who do, somehow, return to school? What of those whose academic careers are never directly interrupted by violence? What kind of education are they receiving? Studies8 suggest that globally, not only are too few students in school, but the level of education received is too low.

Given that nations that suffer conflict are often classified as low or low-middle income, between 91% and 87% of all primary school-age children living in SSA will not achieve MPLs in reading and Mathematics. This compares with 5% to 8% for high-income countries globally.

So, what do the numbers from Table (2) say about Sub-Saharan African (SSA) primary education:

- 87% of primary school-age population are not achieving MPLs, comparing poorly with the 56% global average and the 7% for Northern America and

- While globally 23% of all primary school-age children live in SSA, 36% living in SSA are not

Lost within these figures is the impact of the conflict that states have, and continue to experience.

Education and Peace

If there is one aim that all parties around the world seem to agree on it is the importance of universal access to primary education. Such an aim was stated explicitly in the Millennium Development Goals and Education for All initiatives, aimed at securing primary education for all children by 2015. The continuation of the Millennium initiatives was captured subsequently within the Sustainable Development Goals (2016). Since the adoption of these, the world has seen a 42% drop in the numbers of out-of-school children between the ages of 6 and 11. Girls in the age range have seen a 47% drop10. This represents great progress, but it is clear that the goal was not achieved in its entirety, and those countries in conflict have made the least amount of progress while simultaneously being the home of more than half of out-of-school children.

Part of this problem can be attributed to the nature of political instability itself. The disruptive nature of violence and war preclude serious investment in education. But part of the blame can also be put on the ulterior motives of actors both inside and outside of the countries themselves. Consider that in 2009 countries in conflict, desperately in need of investment, received less than 20% of worldwide educational aid.

One could argue that in situations where cries of violence could easily spiral out of control, the priority is the establishment of long-lasting peace and meeting the basic material needs of the people. To this end, it is important to note that education can be a means to building lasting peace. It is a key component in creating a society that is ‘conflict-resistant’ and equipped with the necessary skills to resolve conflicts in non-violent and equitable ways.

National stability increases as students are equipped with the skills to rebuild not only the economy but also a culture that is conflict resistant. Such skills equip students with the ability to affect a ‘positive peace.’ When examining the absence of armed struggle in a conflict-prone population we often see that a ‘negative peace’ develops. The violence is eliminated, often by force, but the roots of the conflict are still not addressed. Since the central conflict is unresolved and the population has not developed any skills that would make the non-violent redress of their grievances more likely, the violence can become cyclical11.

If properly designed, schools themselves can be a key component in ending this cycle. For that reason, countries should invest heavily in designing and implementing a primary level curriculum that transforms schools into settings where peace is built and maintained. The effectiveness of schools as tools for peace and rehabilitation can be seen most clearly in refugee camps.

For refugee children, school provides not only a way out of a lifetime of poverty but also a return to normalcy. The effect of going to school can be cathartic and provide the kind of emotional support that children affected by conflict and living through chaos need. According to the UNHCR’s 2017 report, Left Behind12, education “… imparts life-saving skills, promotes resilience and self-reliance, and helps to meet the psychological and social needs of children affected by conflict. Education is not a luxury – it is a basic need.”

One way to use the schools as a catalyst for lasting peace and increase the perceived value of sending children to school is also to teach children appropriate skills. In much of Sub-Saharan Africa, nearly half of the family diet is produced by smallholder farms13. These small, mostly subsistence farmers, account for much of the rural population. In places where food insecurity and malnutrition create an added barrier to education, teaching children simple agricultural skills can help keep families fed and make the best use of small plots of land. Additionally, if schools are perceived as valued-added institutions in the community, families will be more likely to enroll their children and keep them attending regularly.

Moreover, teachers are more likely to be diligent in their jobs since they can see firsthand the tangible benefits of their instruction.

Even a cursory examination of educational programmes in conflict-affected areas across Africa confirms the need for alternative educational models. In addition to books and desks, students are in need of supportive services such as sustainable, free-of-charge menstrual hygiene materials for pubescent girls; early literacy kits for the families of primary school children; semi-formal school initiatives that help children transition into formal school; art therapy; sports and life skills programmes.

One of the many detrimental consequences of conflict is that the value of formal education to the family drops significantly. It drops even lower for female students whose labour at home is often valued more than their potential to earn a future income or to make a contribution to the wider community. Thus, many students across many age groups will not matriculate beyond the primary level. For this and many other reasons, in conflict-affected areas it is important for older students that additional elements such as basic financial literacy are added to the curriculum.

Students must be able to access alternative and accelerated educational programmes that are relevant to the social and economic realities of the students and their communities. In 2016, USAID conducted a study14 in the DRC and found that the main reason why respondents were not participating in alternative educational programmes was the perception that they were of little value in real terms; even part-time work was seen as being more valuable.

There is also a matter of timescale when it comes to children whose education is disrupted by conflict. The longer they wait to return to school the more vulnerable they become to human trafficking, recruitment into armed conflict, and early marriage15. Alternative and accelerated educational programmes are vital to the aspirations of any conflict-affected nation.

Children whose education has been interrupted or who have never enrolled in formal schooling can benefit most from such programmes and can hope to one day join their peers in formal educational settings. Rural and impoverished children also benefit from educational programmes that feature localised market skills and flexible class schedules to allow students to offer their labour at home without neglecting their studies. Educators need to recognise that for many of these children, primary education will be the only formal education that they will complete.

It needs to be noted that schools can also be placed at the heart of conflicts. They can reinforce stereotypes, inappropriate narratives and national mythologies that lie at the heart of many conflicts16. In segregated school systems, the schools themselves become one of the many settings that are restricted to some elements of the population.

Bespoke education eliminates much of this problem. By creating parallel education tracks that meet the students where they are, regardless of their circumstances, we create a system that facilitates each student to achieve, even if it takes additional years. The curriculum should not only reinforce the national identity but reflect the students’ faces and culture back to them. The textbooks and learning material should communicate that the place to build their dreams and plan their future is not on foreign shores but in their homelands. The villages, towns, and cities of their nation are not places from which to escape but places where they can build futures and live well.

A school that builds peace and social cohesion needs an approach to education that removes violence and coercion from every aspect of the educational experience. This can be aided by designing texts and a curriculum that shines a light on the long-lasting, pervasive, and destructive effects of using violence and coercion to solve disagreements.

Systems should be implemented that hold teachers accountable for their attendance and conduct while in the class, with sufficient checks and balances to reduce corruption at all levels. Careful attention must be paid to the use of corporal punishment in the classroom. Using violence to discipline children who are already suffering serious emotional and mental stress due to violence either in the home or because of armed conflict is counterproductive17. Corporal punishment will only reinforce the lessons of war, namely that ‘might makes right’ and force is an acceptable method of resolving problems.

To that end, teachers may also need to be reformed and retrained. The expectations, oversight, and procedures dealing with teacher compensation, attendance, conduct, and qualifications must be re- evaluated with different aims; namely, that schools do not just build professionals and business people, but that they should be incubators for a greater, more stable, and secure nation. Primary school education must be responsive to the needs of the local community while supporting a greater, national narrative18.

Unfortunately, many of the abuses and much of the corruption that was commonplace during times of armed conflict have become second nature, even to educators. Although we usually hear about scandals involving corruption at the secondary and tertiary level, the truth is that such behaviour begins in primary schools. The International Institute for Educational Planning estimates that salaries for absentee or ‘ghost’ teachers are as much as 20% of the educational payroll costs in some countries. Many, if not most, of these missing teachers are assigned to primary schools and rural schools, where there is less oversight.

Teachers and administrators alike should be exposed to anti-corruption education like the UN’s Anti- Corruption in Management Education Curriculum19, which has been introduced in Business Schools across Africa, including Nigeria and South Africa, with great results. This should be coupled with regular, in-service training regarding the emotional, psychological, and intellectual needs of students. Teachers should be taught how to spot signs of abuse, neglect, emotional trauma, and intellectual disabilities that may not be obvious at first.

To facilitate this, new schools and new ways of training teachers will need to be implemented. Teaching colleges and local teacher certification programs will be necessary. Investing in teachers and bespoke textbooks is a must.

Building an educational system that is capable of absorbing children whose education has been marked by periods of extreme conflict is a difficult task. Many nuances must be addressed, and a great number of resources must be put in place to do it effectively. However, the cost of failure is even greater and the lasting effects of failure even farther reaching. Alternatively, success offers the future that children deserve.

Conclusion

Nelson Mandela is quoted as saying, “no country can really develop unless its citizens are educated.”

When it comes to education and the future of developing nations whose recent history has been blighted by conflict, it is clear that a new approach is needed. Such an approach needs to provide grassroots solutions to local problems, encourage peace, and provide learning models that exist beyond the traditional western approach. It is in the best interest of all nations that governments make a sustained long-term investment into primary education. This must include bespoke textbooks and other learning materials, and teachers. The overall aim must be child-focused rather than a blind mimicking of current models. The challenges and unique needs of each nation and its children must be the guiding force behind any education reform. The view expressed almost 40 years ago by The Zambia National Council for Book Development (1982)20, that “Africa is facing the perspective of unwittingly using primary education for the production of semi-illiterates,” holds true today. This sentiment is even more profound when dealing with children of conflict.

Instead of making the objective of school to receive high marks on standardized tests, the objective must be the mastery of basic skills that will enable the children to improve their standard of living and provide tangible benefits to their community. Creating a literate and skilled workforce has been the cornerstone of every nation that has seen significant economic growth in the last half-century.

Encouraging the entrepreneurial spirit in the classroom and making access to high-quality, bespoke, primary-level education feasible for both children and adults is arguably the most impactful investment for the future.

1 “Demographic Effects of Girls’ Education in Developing Countries…. ” www.nap.edu/read/24895/chapter/1. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

2 “Redefining Education in the Developing World.” https://ssir.org/articles/entry/redefining_education_in_the_developing_world. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

3 “Numbers out of school children stagnate while aid to basic … – Unesco. https://en.unesco.org/gem- report/sites/gem-report/files/PR_aid_reduction_en3.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan. 2019.

4 “Attacks On Education – Save the Children International. 12 Jul. 2013, www.savethechildren.net/sites/default/files/Attacks%20on%20Education_0.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

5 “CfBT 023_Armed Conflict_full report.indd – Education Development Trust. www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/~/media/EDT/files/research/2014/r-armed-conflict-2014.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan. 2019.

6 “CfBT 023_Armed Conflict_full report.indd – Education Development Trust. www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/~/media/EDT/files/research/2014/r-armed-conflict-2014.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan. 2019.

7 “Educating Girls, Ending Child Marriage – World Bank Group.” 24 Aug. 2017, www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2017/08/22/educating-girls-ending-child-marriage. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

8 “More Than One-Half of Children and Adolescents Are Not Learning…. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs46-more-than-half-children-not-learning-en-2017.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

9 More Than One-Half of Children and Adolescents Are Not Learning…. “http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs46-more-than-half-children-not-learning-en-2017.pdf

10 “Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All | UNICEF Publications…. ” www.unicef.org/publications/index_78718.html. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

11 “(PDF) Conflict, Peace-building, and Education: Rethinking…. www.researchgate.net/publication/315772372_Conflict_Peace- building_and_Education_Rethinking_Pedagogies_in_Divided_Societies_Latin_America_and_around_the_World . Accessed 8 Jan. 2019.

12 “Left Behind – Refugee Education in Crisis – UNHCR.” www.unhcr.org/left-behind/. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

13 “Rural food security, subsistence agriculture, and … – NCBI – NIH.” 19 Oct. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5648179/. Accessed 8 Jan. 2019.

14 “Final Research Report – USAID ECCN.” https://eccnetwork.net/wp- content/uploads/1.27.17_DRCFinal.Links_.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

15 “Child Soldiers, Slavery and the Trafficking of Children – FLASH: The…. ” https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2091&context=ilj. Accessed 8 Jan. 2019.

16 “The Hidden crisis: armed conflict and education; EFA … – Unesdoc.” https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000190743_eng. Accessed 8 Jan. 2019.

17 “Corporal punishment may have long-term negative effects on…. ” 26 Jul. 2011, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/07/110726111109.htm. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

18 “Fixing the Broken Promise of Education For All, Executive Summary.” http://allinschool.org/wp- content/uploads/2015/01/OOSC-EXECUTIVE-Summary-report-EN.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan. 2019.

19 “Anti-corruption guidelines (“Toolkit”) for MBA curriculum change July…. ” www.unprme.org/resource-docs/ComprehensiveAntiCorruptionGuidelinesforCurriculumChange.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

20“Zambia National Council for Book Development – Unesdoc – Unesco.” https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000052588. Accessed 9 Jan. 2019.