Apprenticeships and Entrepreneurship

Effective tools to support the development of human capital and encourage economic progress

Introduction

For the past 20 years the population of Zambia has been racing forward at an annual rate of almost 3%. The official figure for 2017 is 17.5 million.[19] The 4.8 million plus young people aged 15-35 present a substantial opportunity to transform the country by harnessing this ‘demographic human capital.’[6]

Within the formal and informal sectors, broadly defined as enterprises which respectively do and do not comply with the relevant Government laws and regulations, the vast majority (plus 70%) of the national workforce work in the primary sector which contributes less than 10% towards GDP.[9] In addition, more than 90% of the national workforce work in the informal primary sector.[9] These combined elements make the transition of the economic structure, that invariably accompanies economic development, more difficult. Moreover, the level of unemployment amongst young people, who represent 17% of the working population, is high.[15]

As with other sovereign states, Zambia could develop apprenticeship and entrepreneurship programmes as tools to support a changing economic structure and reduce youth unemployment.

The purpose of this paper is to explore how changing economic structure and implementing apprenticeship and entrepreneurship programmes can impact positively the development of Zambian economy and human capital.

Economic structure – significance

Achieving a high and sustainable rate of economic growth is an important rung on the development ladder of a sovereign state and therefore a central aim of governments. With economic growth differing between countries and over time due to factors such as the development and use of human capital, the application of technology, and the nature and extent of investments,[4] economic growth can be conveniently analysed using the changing relative composition of industry sectors (primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary – sometimes combined with tertiary). This in turn can be evaluated with respect to output (contribution to GDP) and capital or labour input.

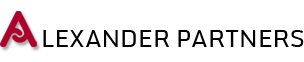

Over time the structure of an economy changes to reflect factors such as changing demographics, application of technology, international competition, and patterns of demand for products and services. The structure of an economy therefore affects output and employment. As an example, with economic growth and rising real income, the demand for goods and services with high and positive elasticities, such as recreation activities, will tend to increase. This in turn will positively impact employment. Figure (1a) provides a summary of the 2016/7 economic structure for Zambia.

Zambian economic structure

Located in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), Zambia is categorised as a least-developed country (LDC). For about 70% of the population agriculture is the mainstay from which between 70% and 77% are identified as poor living in rural areas.[4] In the early 1990s the agricultural sector accounted for more than 60% of Zambia’s total planted area for major crops. Dominated by smallholding farms, this contributed to an average of 18% of GDP.[4]

Endowed in arable land, labour and water resources,[9] landlocked Zambia’s potential market for agricultural produce has been bolstered by membership of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA); the Southern African Development Community (SADC); access to the EU agricultural markets through the Everything but Arms (EBA) initiative; access to the US market through the African Growth Opportunities Act (AGOA).

Zambia, changing economic structure

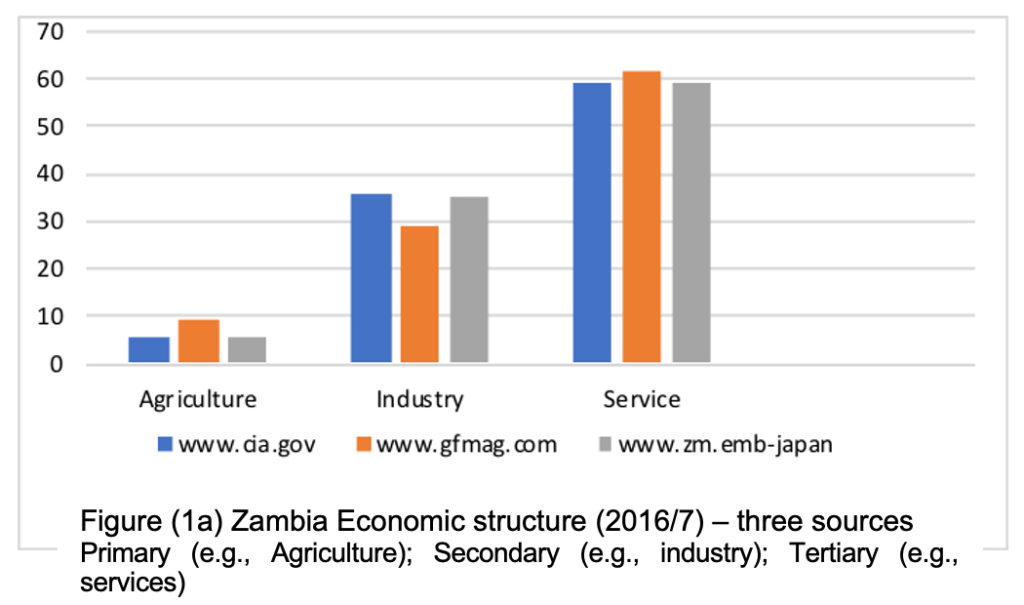

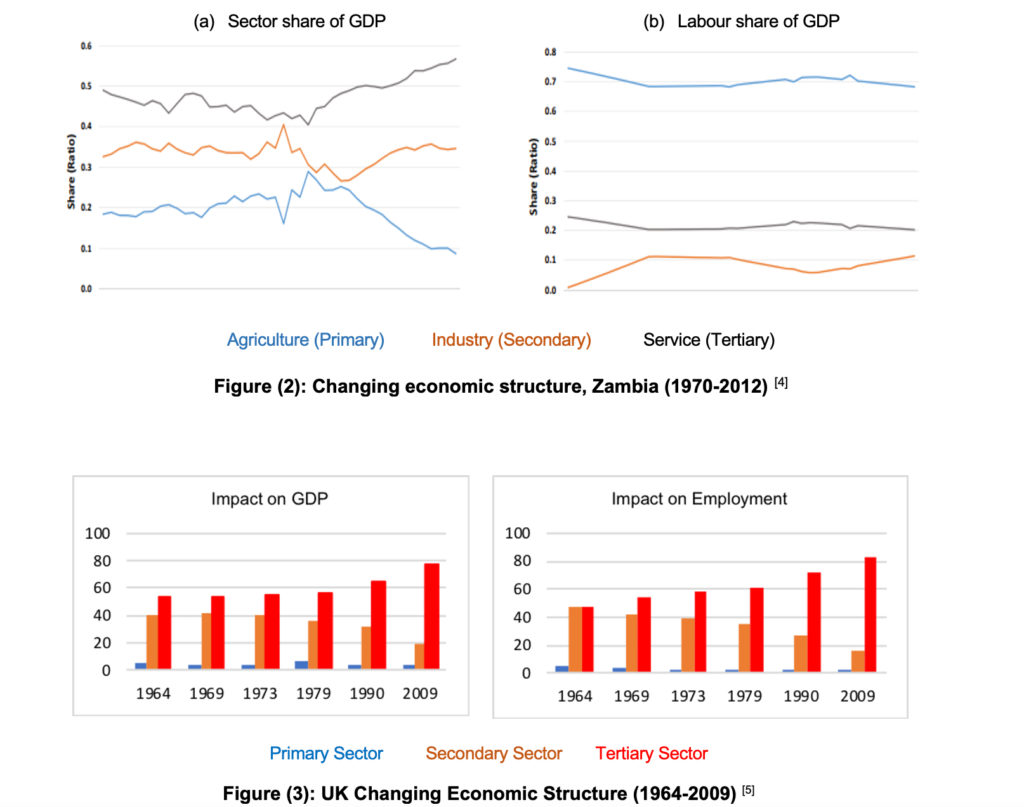

Figure (2) shows the structural transformation experienced by Zambia after 1995; overall, agriculture shrinks whilst industry and services increase. Looking at Zambian employment between 1970 and 2012, the overall trend is that employment declined gradually in agriculture and services but increased in the industry sector. Although nearly 70% of the formal labour force worked in agriculture, this sector contributed only between 10% and 30% to GDP.[4] This is in contrast with an industrialise nation, such as the UK, where the primary sector contributes least to GDP and employs the least number of workers, Figure (3).

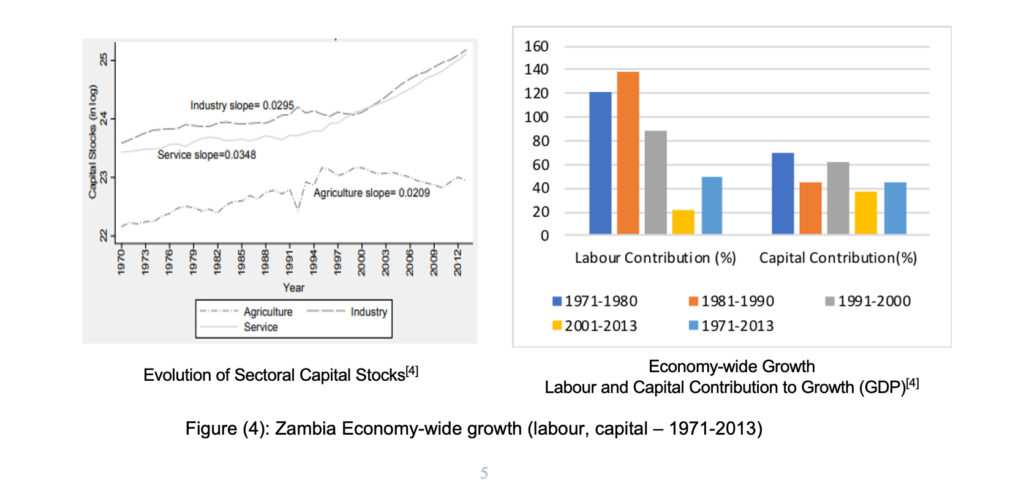

In addition, as can be seen in Figure (4) from about 2000 the rate of growth in total capital (capital stock) for the agriculture sector declined, reflecting a lack of investment. In contrast, both industry and services experienced growth.[4] It is interesting however to note that labour force has a greater contribution to GDP than capital, suggesting that a country such as Zambia should invest preferentially in labour.[4]

A country’s economy is affected by many variables; trade, employment, output. When these are stimulated economic growth and development will alter the economic structure, typically changing the profile that reflects the relative size of the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary sectors. For Zambia, an argument could be made that there could be a greater emphasis on developing the primary and secondary sectors.

Impact of structural economic change

Employment – Manufacturing -v- Service sector

A decline in industrial employment need not be problematic if compensated for by increasing non-industrial employment, possibly in the tertiary sector. However, a decline in manufacturing activity may have a more serious negative employment impact because manufacturing is characterised by more backward linkages than the service sector:

- Compared with service sector gross output, every pound spent on manufacturing gross output create almost three times as much employment income across all sectors.[5]

- Only 13% of innovations are developed in the tertiary sector compared with 87% from primary and secondary combined. Therefore, preferential growth in tertiary, at the expense of other sectors, puts backward and forward-linkages at risk.[5]

- Because of the scope for capital investment and technical progress, manufacturing (a progressive sector) lends itself to rapid growth of labour productivity. In contrast, in parts of the service sector (a stagnant sector where there is no tangible output) there is little scope for improved productivity. Stagnant sector unit costs will therefore tend to increase more rapidly than in a progressive sector.[7]

- Economic growth slows when labour shifts to a stagnant from a progressive sector.[7]

Trade – Balance of payments

Because balance of payment reflects trade and financial transactions between consumers, business, and governments, it aids our understanding of the level and pattern of trade in goods and services across borders. Taking focus on the industry sector, efficient manufacturing should not only satisfy the demands of domestic consumers, off-setting national import requirements, but also supply international markets. This is subject to the requirement that an efficient manufacturing sector has the ability and capacity to achieve these objectives at socially acceptable levels of output, employment, and exchange rates.

Second, because many services cannot be traded internationally, particularly public-sector services, it is unlikely that the service sector can wholly take over the traditional balance of payment role of manufacturing. This point is supported by findings from The House of Commons Trade and Industry Committee (UK) who reported that on average a 2.5% rise in service exports is typically required to offset a 1% fall in manufacturing exports.[5] For Zambia, a too rapid shift in the economic structure towards services could clearly therefore disadvantage the balance of payment.

Output – Productivity

It is accepted that structural economic change is a feature of economic growth and development. It is also recognised that irrespective of industry sector, levers such as education and infrastructure investment are key to economic growth. Therefore, effort and resources directed at increasing productivity should be concentrated preferentially on factors that affect productivity within and not across sectors.

Two main factors are frequently used to explain differences in productivity, or output per head, between countries, namely investment in tangible assets such as plant and machinery, and the quality of labour input (human capital). In the former case infrastructure investment contribution to productivity can be seen in examples such as increased transport investment leading to decreasing transport costs. Regards human capital, being poorly skilled or not adopting better working practices to maximise return on available resources are likely to hamper productivity.[27]

Unemployment and economic structure

Over time a changing economic structure, with associated benefits such as innovation and technological advancement, can also throw up challenges in demand and supply-side unemployment. For Zambia, whether we consider the formal or informal sector, youth unemployment (15-24 year olds) ranges between 13.8% and 17% and remains a significant challenge. The majority of the unemployed lack the education, training, and effective vocational guidance that the work place needs.[9,13,15]

The continued economic slowdown and reduced economic demand experienced by Zambia have contributed to demand and supply-side unemployment, namely workers in-between jobs (frictional), wage demands exceeding what employers are willing to pay, and the skills mismatch between the unemployed and available jobs (structural).[2] It is also to be noted that as Zambia continues to strive for economic growth the associated changes in economic structure, geographic and occupational immobility, globalisation, and even a shift in labour demand pattern are likely to also contribute to structural unemployment.

Policies to reduce supply side unemployment

Various measures are available to governments to reduce the level and impact of unemployment; employment subsidies, facilitate increased geographic mobility; increase and targeted education and training to improve labour market flexibility. Of the many tools, establishing apprenticeship and entrepreneurship type programmes are likely to have a collective over- arching positive influence on unemployment, in particular youth unemployment. It is to be noted however that supply-side policies seek to overcome labour market challenges such as reducing supply-side unemployment rather than boosting demand.

- Develop human capital

- Provide strong incentives (make work pay)

- Occupational and geographic labour mobility

- Stimulate public and private sector demand

- Encourage entrepreneurship and innovation

- Lower employment taxes to increase labour demand

- Improve export competitiveness

Policies to tackle demand and supply side unemployment

Insights from developed economies

Through apprenticeships governments have been able to raise skills level of human capital. Aptly designed apprenticeship schemes; deliver targeted vocational education and training effectively combining work and classroom teaching; support the transition from education to employment; reduce the skills gap between employers and sector needs and so ensure a steady skilled employee pipeline.

Apprenticeship programmes work well in Germany, UK and most other developed economies. However, because historically they are associated with the primary and secondary industry sectors, their success over time mirror the vagaries of economic structural changes towards the tertiary sector. In addition, because they are generally seen as below par with graduate qualifications it is harder to attract the more able students and so difficult for apprenticeships to gain substantial traction.

Apprenticeships

More often than not escaping poverty demands the effective management of economic growth (structural transformation) – developing human capital within industry sectors and transitioning human capital between sectors.[9] For Zambia the primary sector is therefore the most relevant because it employs more than 80% of the national labour force; 97% of whom work in the informal sector.[9] Experience from other countries strongly suggest that Zambia should consider developing apprenticeship programmes as one of the tools to bridge the skills gap within a sector and to drive labour transition between sectors.

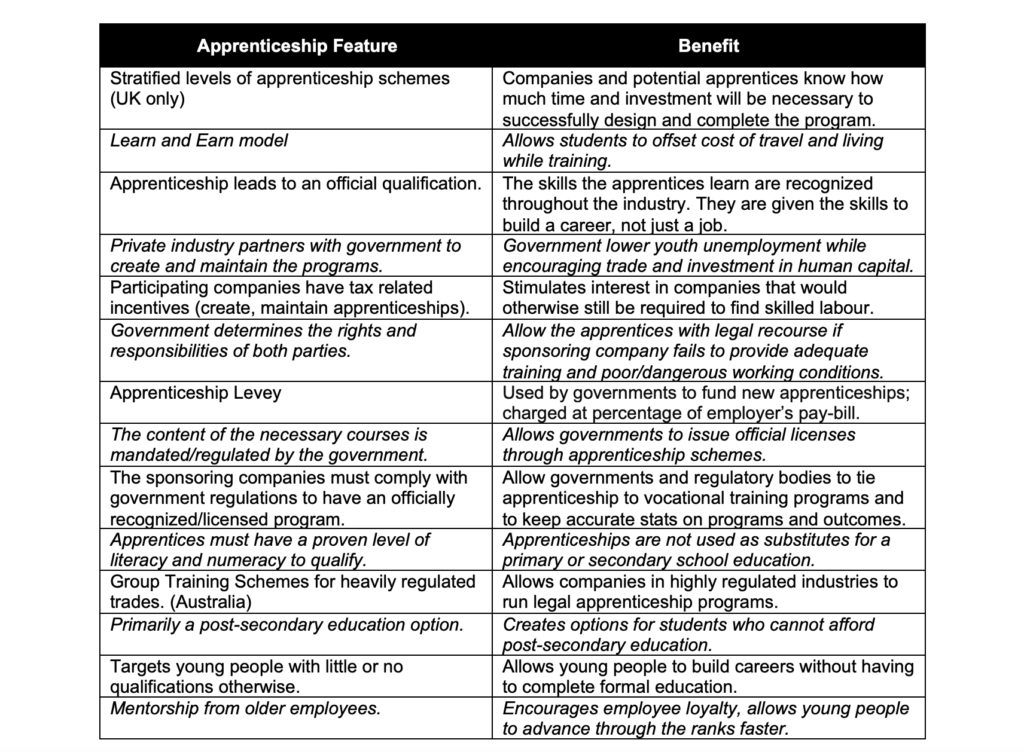

Apprenticeships, Best Practice (Countries examined: USA, Canada, UK, Australia, Austria, Switzerland, France, Germany) [20,21,22,23,24]

Entrepreneurships

Entrepreneurships create jobs, innovate, intensify competition, and have the potential to increase productivity through technological change. Entrepreneurship can thus translate directly into high levels of economic growth.[8, 10, 18] However, when informal self-employment is included in its’ definition high levels may create too few conventional wage-earning job opportunities. In this case, as experienced in Italy, high levels of entrepreneurship can be correlated with slow economic growth and lagging development.[3] Also necessity entrepreneurship, viz being pushed into entrepreneurship because all other options for work are either absent or unsatisfactory, does not have the same effect as opportunity entrepreneurship.[1,17] The ratio of opportunity-to-necessity entrepreneurship can therefore be used as another indicator of economic development.

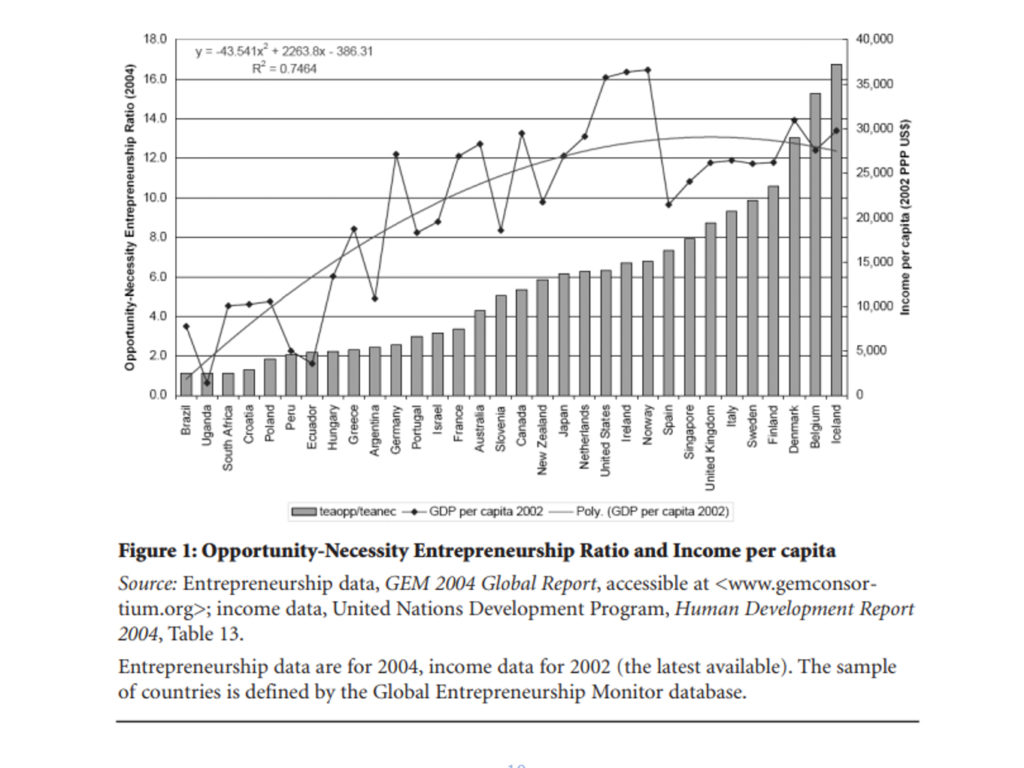

Figure (1) shows a positive relationship between the opportunity/necessity ratio and GDP per capita. A strong inference here is that for economies in the early or middle stage of development (Uganda, Peru, Argentina) entrepreneurial activity can negatively impact economic development. In part this is because most of the working population have low income and often strive to move from self to wage employment. At the other end, Germany, France, Finland, display high income and low levels of entrepreneurial activity. Two outliers are Japan and the U.S, with one of the lowest and highest levels of entrepreneurial activities, respectively. Discounting these outliers there is a clear discernible trend between the ratio of opportunity-to-necessity entrepreneurship and per capita income.

In most cases necessary entrepreneurship, either in agriculture or very small-scale industry, will not lead to economic development (higher growth rates) because there are far fewer mechanisms to link the activities to development. However, as more of the working population migrate from necessary to opportunity entrepreneurship, economic development is likely to rise and unemployment fall.[17]

Entrepreneurship and economic growth

There are fine differences between small business owners and entrepreneurs. Typically, the former usually deals with known and established products and services (known risks) while entrepreneurial ventures focus on opportunities (unknown risks). In addition, a small business usually aims for modest growth and continued profit whilst entrepreneurial ventures target rapid growth and high returns. As a direct consequence and even after taking into consideration global geographic variations, entrepreneurial ventures generally have a more positive impactful and cascading influence on economies.[14]

Solution for Zambia

Zambia’s national strategy, in pursuant of its’ economic development plan, could greatly benefit from including the formalisation of a significant portion of its large, vibrant, and informal MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) business sector. Entrepreneurship is an effective tool to achieve this – the Zambian Development Agency (ZDA) is charged, in part, with this responsibility.[11,12]

The need for economic development and the increasing growing concerns around Zambian youth unemployment should be strong motivators to encourage and support the growth of opportunity-entrepreneurship. Further, entrepreneurship directed at gaining the most from Zambia’s abundant natural resources will help to shift the economic structure away from principally supplying commodities towards increasingly producing high value goods. Attaining specific ratios between opportunity-necessary entrepreneurship, and formal-informal business can therefore help to stimulate job creation and thus economic development.

- Develop people-centred strategies to facilitate transition of critical number of primary and secondary sector MSMES from informal to formal status.

- Encourage companies to invest in vocational training, entrepreneurship, apprenticeships by establishing industry focused skills, competencies, and standards.

- Develop laws such as copyright, patents, consumer protection that encourage entrepreneurship and protect business owner and the consumer.

- Maintain and expand key infrastructure.

Role of government in developing and encouraging entrepreneurship

Concluding remarks

Changes in the economic structure of Zambia are typical of a LDC that is rich in natural resources and pursue infrastructure development. It therefore means that by following the traditional route to industrialisation, the task of transposing a significant workforce from the primary into the secondary and tertiary sectors presents both economic and social difficulties.

Weighty challenges include, generally how best to develop the significant labour capital (historically Zambia’s labour productivity is much lower than regional competitors such as Kenya, Botswana[1]) and, specifically within the primary sector whilst increasing overall GDP and contribution to GDP from the primary and secondary sectors.

In summary, Zambia could look to develop targeted apprenticeship schemes, achieving critical ratios for both opportunity-necessary entrepreneurship and formal-informal enterprises to spur job creation and thus develop the economy. Whilst there is a clear need for investment in both capital and labour, the latter will have a greater impact on GDP. In addition, investment in the tertiary sector will have less impact on GDP and employment than investments in the secondary and primary sectors.

| Cassava dried farming crops, Mansa Zambia (Source – Tom Chiponge Baroque M.C from pixabay) |

Citations

- The profile and productivity of Zambian businesses, Zambia Business Survey, June 2010 (http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/949481468170956721/pdf/698090v-10ESW00ivity000final0report.pdf)

- Types of unemployment (https://.economicshelp.org/blog/716/unemployment/types-of-unemployment/)

- Why entrepreneurs are important for the economy, Shobhit Seth, 2017 (hhtps://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/101414/why-entrepreneurs-are-important-economy.asp)

- Sources of economic growth in Zambia, 1970-2013: A growth accounting approach, May 2017, Kelvin Murunga and John N. Ng’ombe (Economies2017, 5(2), 15; https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5020015)

- Changes in the economic structure (https://catalogue.pearsoned.co.uk/assets/hip/gb/hip_gb_pearsonhighered/samplechapter/0273736906.pdf)

- Xambia’s young people and the road to 2030, 12 August 2016 (http://zambia.unfpa.org/en/news/zambia%E2%80%99s-young-people-and-road-2030)

- William J. Baumol, Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: The anatomy of urban crisis: The American economic review, vol.57, No.3 (Jun.1967), pp.415-426

- Audretsch, D. and R. Thurik (2001) Linking entrepreneurship to growth, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2001/02, OECD Publishing, Paris (http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/736170038056)

- The informal sector in Zambia, International Growth Centre (IGC), June 2012 (https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Kedia-Shah-2012-Working-Paper.pdf)

- Harshana Kasseeah, (2016), Investigating the impact of entrepreneurship on economic development: a regional analysis. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 23 Issue 3, pp.896-916 (https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2015-0130)

- Entrepreneurship in Africa being used as a tool for job and wealth creation-Veep, January 26, 2017 (http://www.lusakatimes.com/2017/01/26/entrepreneurship-in-africa-being-used-as-a-tool-for-job-and-wealth-creation-veep/)

- What is the condition of entrepreneurship in Zambia? May, 2017 (http://smeaccountingservices.com/condition-entreprenuership-zambia/)

- Zambia: Unemployment rate from 2007 to 2017 (http://www.ststidta.com/statistics/809085/unemployment-rate-in-zambia/)

- Why entrepreneurs are important for the economy (https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/101414/why-entrepreneurs-are-important-economy.asp#ixzz5G8InIpL2)

- Youth unemployment is at 16.3%-CSO, September 2017 (https://diggers.news/business/2017/09/28/youth-unemployment-is-at-16-3-cso/)

- (a) Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbbok/fields/2012.html)

(b) Global Finance, Zambia GDP and Economic Data (https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/country-data/zambia-gdp-country-report)

(c) Macro-economics of Zambia, August 2017

(https://www.zm.emb-japan.go.jp/files/000293216.pdf)

- How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Zoltan Acs, School of Public Policy at George Mason University, 2006 (https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/itgg.2006.1.1.97)

- The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth, October 2017 (https://.vanguardngr.com/2016/10impact-entrepreneurship-economic-growth-development/)

- https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/zambia-demographics/

- Mirza-Davies, J. (2015, March). A short history of apprenticeships in England: from medieval craft guilds to the twenty-first century. Retrieved May 2018, from Houses of Commons Library: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/economy-business/work-incomes/a-short-history-of-apprenticeships-in-england-from-medieval-craft-guilds-to-the-twenty-first-century/

- Canadian Apprenticeship Forum (CAF). The Challenge to Finding and Employer Sponsor Final Report (March 2010).

- Canadian Apprenticeship Forum (CAF). The Link Between Essential Skills and Apprenticeship Training. An Analysis of Selected Essential Skills Initiatives in Apprenticeship Across Canada (June 2007).

- Apprenticeships in the United States, Economic History Association

Daniel Jacoby, University of Washington, Bothell

(https://eh.net/encyclopedia/apprenticeship-in-the-united-states/)

- The Bottom Line: Apprenticeships are Good for Business, Sarah Ayres Steinberg and Ben Schwartz Posted, July 14. 2014

- The Benefits and Costs of Apprenticeship: A Business Perspective United States Department of Commerce, November 2016

- OECD/FAO (2016), “Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: Prospects and challenges for the next decade”, in OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016-2025, OECD Publishing, Paris

- Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform 2009, UK